Most of us know by now that generative AI can promote stereotypes based on biased data. Yet even when the training data is saturated with perfectly accurate representations—and little to no inaccurate ones—the results can still be biased. Why is this so?

To demonstrate this, I prompted an image generator for two of the most frequently reproduced (and misunderstood) artworks by the “Old Masters”: Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man and Andrea Mantegna’s Dead Christ (also known as The Lamentation of Christ). I chose these not just because they are common illustrations of Renaissance concepts, but because the common explanations of them are often misleading or wrong.

It’s hard to imagine a drawing more ubiquitous than da Vinci’s spread-eagled figure in a square and circle. On dorm walls, t-shirts, and Instagram he’s a poster child for the idea that the human form conforms to natural laws. Art collector Nico Franz writes, “The drawing illustrates the ancient insight that the dimensions of the individual limbs of a human being follow mathematical laws,” while exercise guru Daru Strong opines, “The drawing illustrates the perfect proportions of the human figure, with the arms and legs outstretched to fit within a circle and a square….Overall, the Vitruvian Man symbolizes the pursuit of perfection, the harmony between man and his environment, and the unity of art and science.”

Conversely, the Vitruvian Man also a whipping post for lazy humanities scholars lamenting the subjugation of humanity to Platonic ideals or rigid systems, associating it with eugenics and universalism.

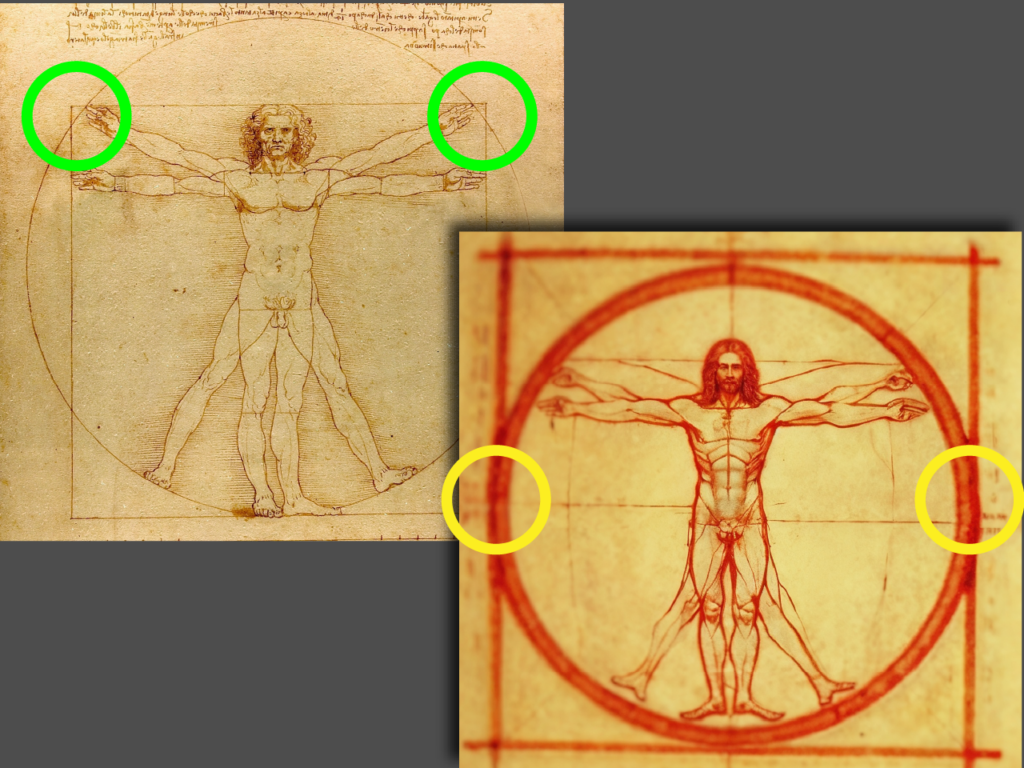

The problem with both fanboys and critics is that they haven’t looked closely at the image. Despite its association with the Roman architect Vitruvius’ definition of ideal proportions, Leonardo’s drawing explicitly departs from its namesake in showing how a human figure—even a non-disabled white male—deviates from mathematical ideals. The span of his arms and legs prevents the square from being precisely inscribed in the circle or vice versa, which is why the square and circle only intersect at the very bottom.

The problem with both fanboys and critics is that they haven’t looked closely at the image. Despite its association with the Roman architect Vitruvius’ definition of ideal proportions, Leonardo’s drawing explicitly departs from its namesake in showing how a human figure—even a non-disabled white male—deviates from mathematical ideals. The span of his arms and legs prevents the square from being precisely inscribed in the circle or vice versa, which is why the square and circle only intersect at the very bottom.

Similarly, Mantegna’s foreshortened Christ is often the amateur art historian’s go-to illustration of the idea of perspective. Its Wikipedia entry devotes an entire Use of Perspective section to how “the realism and tragedy of the scene are enhanced by the perspective.”

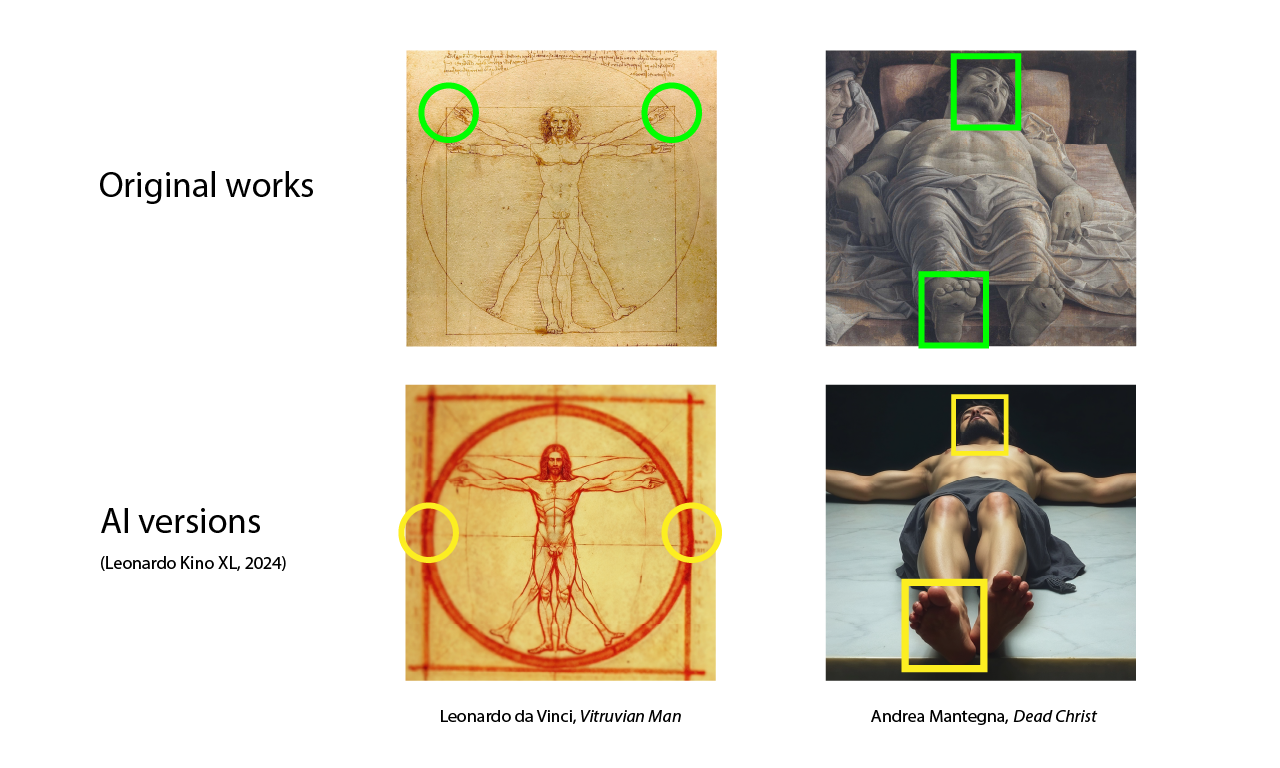

But Mantegna’s Christ isn’t in perspective. The head is just as big as the feet despite being further away, and the figure’s orthogonals do not converge to vanishing points on the horizon, which is the basis of Albertian perspective. This is a deliberate choice on Mantegna’s part to bring you up close and personal with the holy cadaver.

Yes, generative AI has historically had trouble with spatial reasoning, but that’s not the problem here. The AI Jesus displays textbook perspective—just not Mantegna’s distinctive twist on it.

Lazy minds can transform contextual specifics into undeserved generalizations, a process that can be supercharged by confirmation bias—and AI. Kimberly Pace Becker calls this invisible drift, noting that “AI systems, designed to optimize for relevance and clarity, can inadvertently strip away important context and nuance.”

As an experiment, I tried to reproduce these two Renaissance images by prompting AI for the artworks themselves using the most fully featured image generator on the market (with the ironic name Leonardo.ai). The best I could conjure after dozens of iterations simply exemplified the incorrect cliches associated with the textual misunderstandings of the works rather than their visual reality.

Although I never said anything about perspective or squares inscribed in circles, Leonardo.ai gave Jesus a smaller head and fit the Vitruvian Man perfectly into his geometric prison. The results are all the more disturbing because the proportion of inaccurate versions of these images in training data is vanishingly small compared to the number of accurate reproductions.

Clearly the problem in this case isn’t tainted data in the visual record. Rather, it’s easier to explain these errors by the way AI follows the average “drift” of human thought rather than reflecting ground truth.