This week we lost a figure known as “the dean of American avant-garde film.” Ken Jacobs was renowned for his ability to turn the humblest materia prima of cinema, including 16mm projectors and dusty reels of found footage, into optical sorcery. In so doing, he also turned time-honored assumptions about media preservation on their head.

I first met Ken when I organized a 2001 Guggenheim conference called Preserving the Immaterial. This was the first conference on “variable media,” the then-iconoclastic idea that the experience of a work is more important to preserve than its atoms.

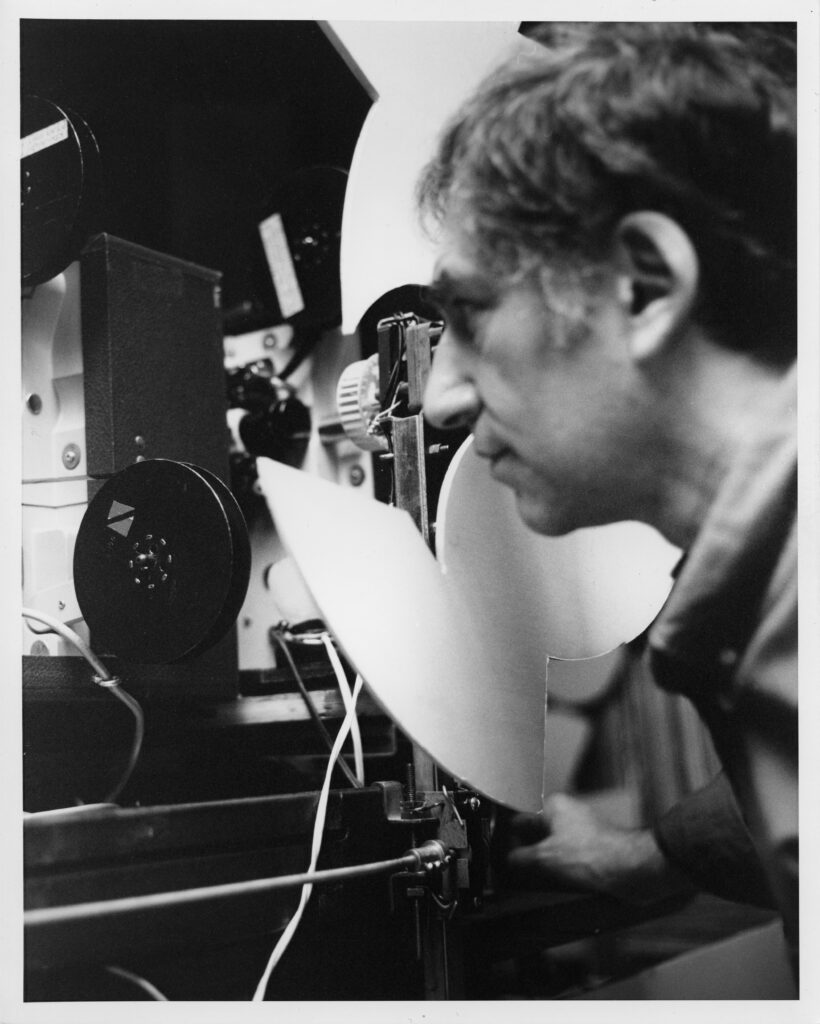

Even by the unruly standards of experimental film, Jacob’s works were especially resistant to traditional archiving. Bitemporal Vision: The Sea (1994) entrained two 16mm projectors outfitted with strobe propellers to cast nearly identical images of waves breaking onto the same screen. Jacobs stood beside the projectors, nudging frames of film up and down, altering timing by fractions of a second. Each adjustment made the waves on the screen seem to oscillate, a hypnotic result that wasn’t quite 2D or 3D but something Jacobs called “two-and-a-half-D.”

I wasn’t surprised when Jacobs bristled at the idea of Bitemporal Vision being reduced to mere video recordings. “It’s totally unkosher,” he told interviewer John Gartenberg at the conference. “This is all about film. How could it be video?” When we played a videotape of his performance the night before, he found it coarse, frustrating. “My details are all mooshed over,” he lamented. “You don’t see these tiny dots struggling for their momentary existence.”

Jacobs recognized the irony that his own experiment in reanimation—giving dead film a new perceptual life—could never fully survive translation into another medium. And yet, even he noticed that digital reproduction introduced unexpected qualities: the heightened contrast and different light of video projection created new spatial effects.

It was precisely this conundrum that made Jacobs such an important figure for those of us grappling with the variable media approach to preservation. His work made clear that safeguarding an artwork wasn’t just about storing objects but preserving behaviors. You could house the reels of Bitemporal Vision in perfect conditions forever, but without the dual projectors, the darkened room, and a performer’s hands at the controls, the piece would remain inert. His performances reminded museums that an artwork’s “life” might reside in the act of showing, not the thing shown.

It was precisely this conundrum that made Jacobs such an important figure for those of us grappling with the variable media approach to preservation. His work made clear that safeguarding an artwork wasn’t just about storing objects but preserving behaviors. You could house the reels of Bitemporal Vision in perfect conditions forever, but without the dual projectors, the darkened room, and a performer’s hands at the controls, the piece would remain inert. His performances reminded museums that an artwork’s “life” might reside in the act of showing, not the thing shown.

In the end Jacobs was inspired to explore how his aesthetic might propagate via future technologies. His process for producing Flo Rounds a Corner, a collaboration with the New York-based media lab HarvestWorks, was digital from the start. The results were comparable to Bitemporal Vision but also took advantage of subtle visual effects made possible with video editing.

And Ken, for all his seriousness about the machinery of vision, had a disarming sense of humor. Once, he mailed me a box of absurd Chinese action movies he’d scavenged on Canal Street—proof that, despite his cerebral reputation, he delighted in the whole spectrum of moving images, from the sublime to the ridiculous.

Ken Jacobs bridged eras of the moving image, splicing together the tactile era of film and the immaterial promise of the digital. In doing so, he reminded us that art’s endurance may lie not in what can be fixed, but in what keeps moving.

You can find more of Jacobs’s reflections in Permanence Through Change, where he joins John Gartenberg, John Hanhardt, and Stephen Vitiello for a conversation about his work. It’s one of a dozen case studies in this free publication that explore variable media preservation applied to everything from websites to stick spirals.

Shown: Ken Jacobs inspecting one of his projectors, ca. 1995. Still from Flo Rounds a Corner.