When he died last Wednesday, artist Mel Bochner left a body of work that’s gained in relevance in a half century defined by information—even more so in the age of AI.

The artist’s death holds special meaning for me because he was a mentor when I was in graduate school at the Yale School of Art. But it’s also an occasion to remember the crucial difference between the strain of conceptual art practiced by Bochner and his peers and a popularized version of the term that persists today. Contrary to the impression that ideas are the essence of conceptual art, Bochner’s work was never about conveying information but about pointing out glitches in that conveyance.

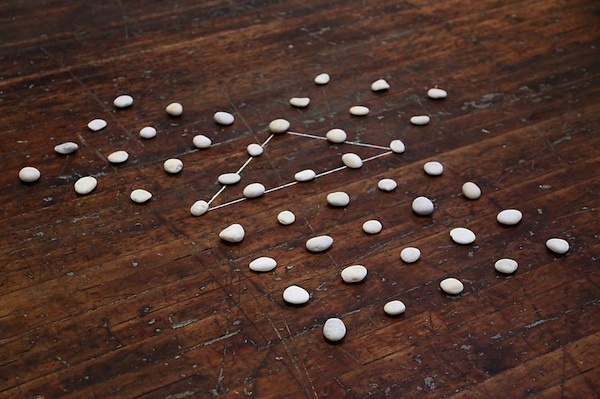

His installations often present what seem like simple facts, only to unravel upon closer inspection. A Polaroid of a ruler labeled “12 inches” seems factual—until we remember that photographs have no fixed scale. A diagram of the Pythagorean Theorem made with stones somehow disproves the truism that the area of squares formed from the two shortest sides must add up to the area of the longest side. (Go ahead, count up the rocks and ask yourself why this mathematical mainstay doesn’t survive translation to the real world). These aren’t parlor tricks; they’re expeditions along the precarious bridge between abstract systems and material reality that expose the rift between them.

As a grad student in the 1980s, I heard my peers spout semiotics and simulacra in an attempt to defend their work using trending vocabulary of the time. More than any other faculty member, Bochner cut through this verbal distraction like a knife, helping us see the gap between what we were doing and what we said we were doing. (I wonder if the prevalence of this artspeak inspired Bochner’s later paintings and site-specific works emblazoned with “blah blah blah.”) This fundamental incommensurability of theory and reality, not some platonic idea conveyed via a neutral, unvarnished medium, is what I see as the most valuable revelation of the artist, and of conceptual art in general.

As a grad student in the 1980s, I heard my peers spout semiotics and simulacra in an attempt to defend their work using trending vocabulary of the time. More than any other faculty member, Bochner cut through this verbal distraction like a knife, helping us see the gap between what we were doing and what we said we were doing. (I wonder if the prevalence of this artspeak inspired Bochner’s later paintings and site-specific works emblazoned with “blah blah blah.”) This fundamental incommensurability of theory and reality, not some platonic idea conveyed via a neutral, unvarnished medium, is what I see as the most valuable revelation of the artist, and of conceptual art in general.

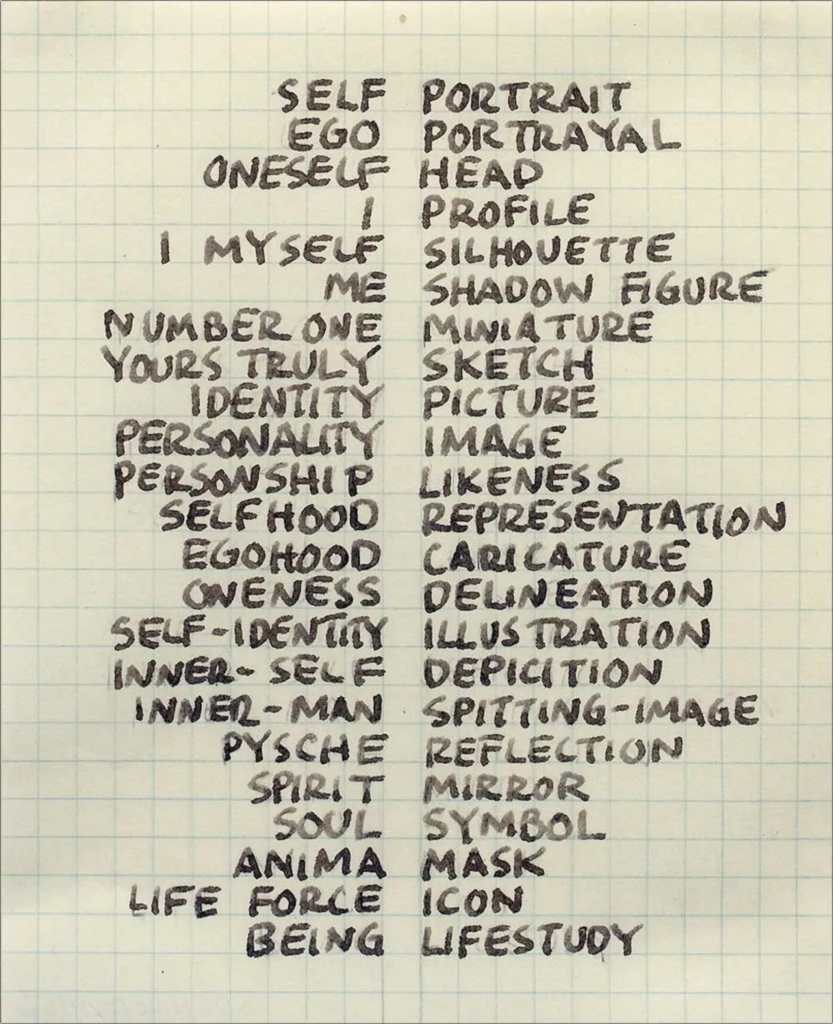

Words are our most pervasive bridge between thought and reality, but this bridge is also shaky—a theme that persisted throughout the artist’s career. Bochner’s word sequences stretch across walls, fold into labyrinths, and spiral into circles, hinting at but never delivering meaning. Probably his most famous dictum is “Language is not transparent,” a provocation he wrote on a gallery wall in 1970.

Fast-forward to 2025 and every task from image-making to healthcare to governance seems about to be handed over to a large language model whose fundamental task is to complete the next word based on previous words in a sequence. If there was ever an epitome of Bochner’s dictum, it is generative AI, for which even the workings of even so-called “open-source” models are completely opaque. As if to confirm the analogy, the column of words in his 1966 self-portrait reads like the raw outputs (logits) of a chatbot, missing only the probabilities associated with each word pair.

AI is increasingly being used to generate everything from news stories to legal documents, yet the average user has no way of verifying the reliability of these texts. The same tools that create realistic images also fabricate political deepfakes; an image of Taylor Swift wearing a “Swifties for Trump” t-shirt is no more reliable than Bochner’s photo of a ruler labeled “12 inches.” AI-written medical advice looks professional but may contain life-threatening inaccuracies; a notorious result of Google’s AI Overview rollout was its recommendation to “eat at least one small rock a day.” Like Bochner’s rocks, these systems claim precision but contain unexamined errors that shape real-world outcomes.

AI is increasingly being used to generate everything from news stories to legal documents, yet the average user has no way of verifying the reliability of these texts. The same tools that create realistic images also fabricate political deepfakes; an image of Taylor Swift wearing a “Swifties for Trump” t-shirt is no more reliable than Bochner’s photo of a ruler labeled “12 inches.” AI-written medical advice looks professional but may contain life-threatening inaccuracies; a notorious result of Google’s AI Overview rollout was its recommendation to “eat at least one small rock a day.” Like Bochner’s rocks, these systems claim precision but contain unexamined errors that shape real-world outcomes.

In today’s world, Mel Bochner’s work feels less like a relic of conceptual art and more like a training manual for navigating misinformation. His art insists that we not take measurements, appearances, and even language at face value. “Look closer,” his work says—and we should.

From the top: Language Is Not Opaque (1970), re-created by the artist at the Jewish Museum in 2014; Meditation on the Theorem of Pythagoras (1972); Self-portrait (1966).