There are challenges to forming a harmonious community. But one thing everyone can agree on is the importance of food.

There are challenges to forming a harmonious community. But one thing everyone can agree on is the importance of food.

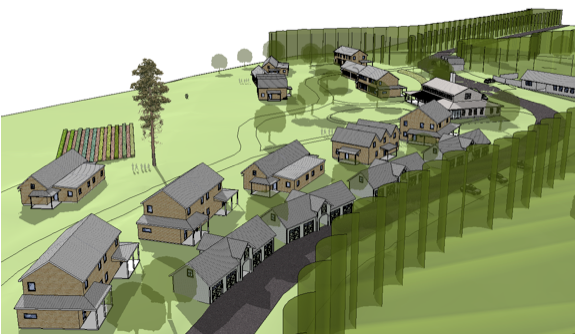

While the local food movement encourages us to shop within a hundred-mile radius, at Belfast Cohousing & Ecovillage, we have the opportunity to produce hundred-yard food. If we wanted to, we could plant raspberry ‘sharing’ bushes between neighbors yards, spiral herbs outside our kitchen doors, alternate apple and peach trees along the driveway, and dangle grapes and kiwi from the Common House trellis. And if knowing your farmer is key to food security, being your own farmer (even for just a blueberry bush or apple tree) is even better, because then we know what it means to generate life, food and community.

To accomplish our goal for community-based food, we consulted a local guru with an international reputation in soil, crop, and forage nutrition, and an expertise in transitioning agriculture for peak oil, climate change and economic drift: Mark Fulford. At our March 11 Open House we asked Mark if we could feed our 36 households on our 42 acres. Mark told us that he has seen many communities in developing countries do this with fewer acres and poorer soil. Then he smiled and said, for you it’s possible, but “there’s a steep learning curve.” Undaunted we asked him to walk with us over the land to show us how.

Based on an inspection of wintered-over and trampled weeds, Mark pointed out our rich Marlow soils ideal for annual vegetable gardens, our ericaceous soils suited for berry bushes, and our clay-covered glacial till that would need some amending for the highest nutrition polycultures or orchards.

Based on an inspection of wintered-over and trampled weeds, Mark pointed out our rich Marlow soils ideal for annual vegetable gardens, our ericaceous soils suited for berry bushes, and our clay-covered glacial till that would need some amending for the highest nutrition polycultures or orchards.

After walking the land, Mark presented a slide show for visitors in which he outlined some strategies for reconnecting people and food. You begin with “a fearless moral inventory of your fridge.” What are you eating, why, and what do you really need to grow? On the other hand, he cautioned “the struggle against nature is costly.” So perhaps eating melons in January is possible, but takes lots of time, energy and money to accomplish. Whereas in Maine, eating kale in December requires only dropping a few seeds in where the September squash is harvested. Listen, he advised, “the crop will teach you.” And he suggested that the overall goal of food production is to “move energy in beneficial patterns.”

Mark was clear about encouraging the entire community to support farmers, learn permaculture skills, develop food processing and cooking skills, and also encourage each member to pursue his and her own relationship to the land and to food, from a family berry patch to a community orchard. He also cautioned against selling off our natural wealth by producing food for the market outside of our community. “That’s how small CSAs lose their wealth, they sell off their natural capital for money.” When asked for an alternative, he replied that for individuals and for communities “the kitchen garden is the model of design and health…no money changes hands. That’s how communities feed themselves in the rest of the world.” Maybe the benefit here is not just economic or ecological, but also cultural.

Mark was clear about encouraging the entire community to support farmers, learn permaculture skills, develop food processing and cooking skills, and also encourage each member to pursue his and her own relationship to the land and to food, from a family berry patch to a community orchard. He also cautioned against selling off our natural wealth by producing food for the market outside of our community. “That’s how small CSAs lose their wealth, they sell off their natural capital for money.” When asked for an alternative, he replied that for individuals and for communities “the kitchen garden is the model of design and health…no money changes hands. That’s how communities feed themselves in the rest of the world.” Maybe the benefit here is not just economic or ecological, but also cultural.

As Japanese polyculture pioneer Masanobu Fukuoka reminds us: “The ultimate goal of farming is not the growing of crops, but the cultivation and perfection of human beings.” Maybe that’s a steep learning curve if we’re all alone, but by growing together, perhaps we can make the arduous climb feel much more like a pleasant afternoon hike.