Diversity without cacophony

Group discussions on controversial subjects can open students to more viewpoints, but they can also result in the usual suspects—sometimes the most thoughtful students, but often just the loudmouths—dominating the conversation. So I was intrigued when Greg Nelson and Rotem Landesman, my collaborators on a course that examines in-depth the impact of AI on writers and creators, proposed a “think-pair-merge” process to distill the best ethical guidelines from a class of 50 undergraduates.

A tournament of ideas

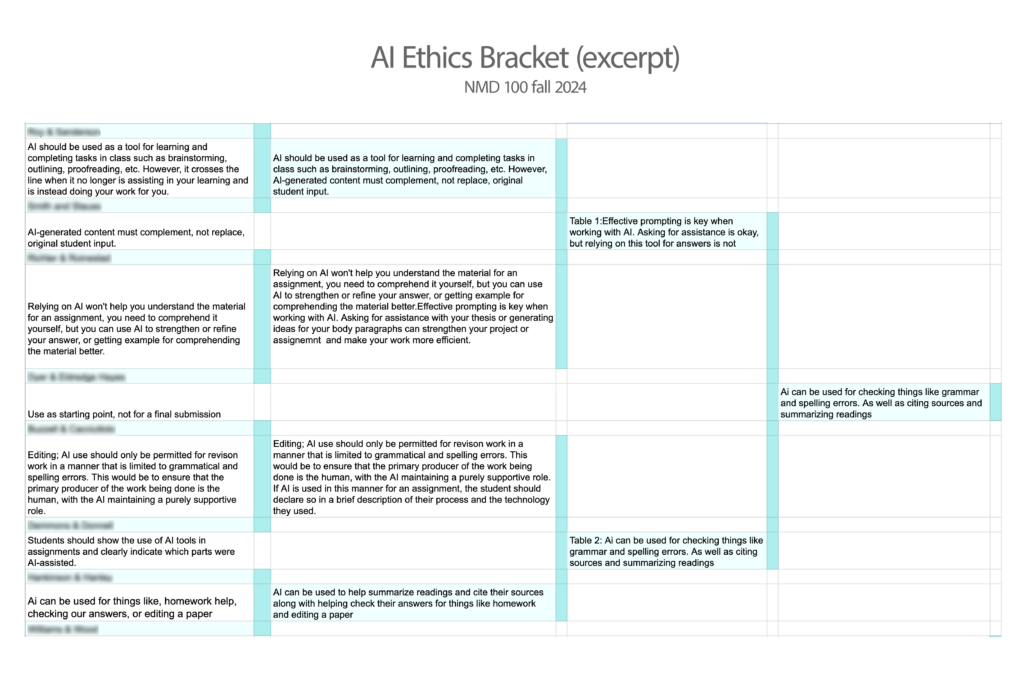

Although the goal was to elevate the best ideas from all the students in a methodical and fair process, our tournament was more collaborative than competitive. To start, each student took five minutes to brainstorm five policies for using AI in their major, along with a brief explanation of why each rule mattered. This solo exercise gave us a diverse initial foundation–up to 250 different ideas–and ensured that no “player” started from scratch in the collaborative rounds to come.

From there, students paired up to share their policies. They debated their merits, identified overlaps, and decided on a single policy to advance. (Is it more important to require AI attribution or check AI-generated sources?) Some pairs merged two ideas into a cohesive rule, while others championed one standout policy. This step required students to articulate their reasoning clearly and find common ground when disagreements arose—an essential exercise in ethical deliberation.

Once pairs finalized their policies, they recorded them in a shared class bracket on Google Sheets. (Thankfully, I found a script that more-or-less auto-generated tournament brackets from a list of student names.)

The next stage ramped up the collaboration as pairs joined each other at tables numbered to correspond to the next brackets. Here, students presented their chosen policies and began the challenging task of synthesizing ideas at scale. They discussed commonalities, negotiated differences, and refined their policies on whiteboards before adding their final choice to the bracket. The discussions were spirited, with some groups grappling with tough decisions about which ethical dimensions to prioritize.

The final four

While the ultimate goal was to arrive at a single class-wide policy, time constraints meant we stopped at the semi-finals, leaving us with four strong contenders:

“AI can be used for checking things like grammar and spelling errors. As well as finding citations and summarizing readings.”

“Unless allowed to, using AI in a graded assignment or a research source results in a failing grade; when allowed attribution is required when using generative AI, of both the model and of the source material. When AI is used for research the sources the AI found should be double checked.”

“AI should be appropriate for organization for projects/ papers depending on if the professor is pro AI or not. If the professor uses AI to design their course then students should have the ability to use it for organization. ”

“Clearly define and educate students on proper AI use, which incentivizes working together and leaves AI suggestions and aid as an option”

I was especially happy to see the “fair dealing” policy, which reminded me of a proposal developed by Lance Eaton’s students at College Unbound requiring faculty to adhere to a similar standard as students. We wrapped up with an all-class discussion about any worthy “Cinderella” policies that didn’t make it into the final four, then ended with a reflection exercise in which students revisited their original policies and considered how their views evolved through the collaborative process.

Student stances towards AI

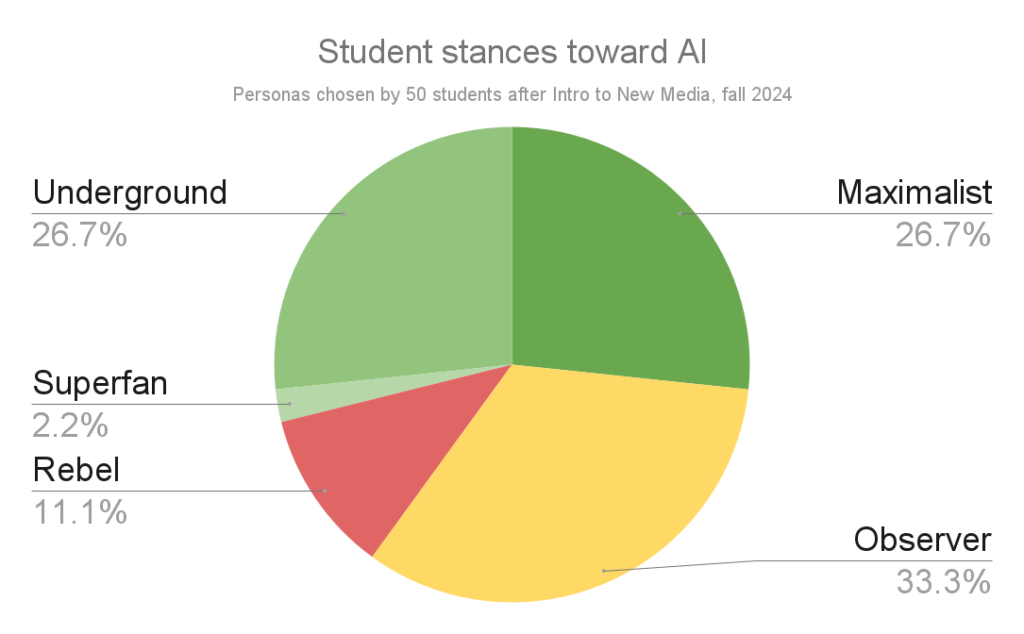

Following this exercise, the same cohort later took a simple quiz to identify themselves as one of five “AI personas.” Although the course’s emphasis on exposure to AI ethics and methods may have skewed the results, just over half the students identified as overt or covert AI power users, while another third are taking a “wait-and-see” approach. A handful of students, perhaps convinced by the ethical quandaries raised in the class, remain resistant to all AI use.

Following this exercise, the same cohort later took a simple quiz to identify themselves as one of five “AI personas.” Although the course’s emphasis on exposure to AI ethics and methods may have skewed the results, just over half the students identified as overt or covert AI power users, while another third are taking a “wait-and-see” approach. A handful of students, perhaps convinced by the ethical quandaries raised in the class, remain resistant to all AI use.

More research to come

The exercise was part of the second annual installment of Introduction to New Media, an ongoing collaboration between Nelson and fellow Computer Science faculty Troy Schotter and me. We asked 100 undergrads to do eight tasks, first with conventional tools and then with AI. For example, after writing an essay in the first week, students get AI feedback on their original drafts, then ask AI for help with feedback, brainstorming, drafting, or polishing a similar essay in the second week. Students then write a detailed comparison of the two drafts. Over the rest of the term, the class repeats this process for creating illustrations, designing logos, coding game avatars, writing stories, creating 3d models, recording soundscapes, and other media. We hope to publish the results of this study in the coming months.